On

my own "must read" stack has been sitting the "2014 Anti-Bribery

and Corruption Benchmarking Report, Untangling the Web of Risk and

Compliance," ("ABC Report") by Kroll and Compliance Week. While I have

read a multitude of bribery and corruption enforcement summaries, mostly

published by law and audit firms, this was my first read of a compliance benchmarking

report. Interestingly enough, upon completion, I thought about whether sharing

my own experience and perspective with respect to the findings could actually

add any value or relevancy to what is already an impressive and extensive

report.

Accordingly,

a disclaimer: When I think about the experience and expertise of Kroll and

Compliance Week, along with the resources deployed to publish this report, I

call attention to my own viewpoint as intersecting but a small part of the

overall scope of their collaborative effort. Hence, when I reflect on the

report’s findings, it is solely in the context of my own experience with third

party intermediaries, as a subset of third party vendors, and anti-bribery

compliance as a subset of corporate compliance. In other words, my personal

familiarity only overlaps some of the many issues covered in the Benchmarking

Report.

As

the ABC Report states in the introduction "we hope you find the

information here useful and that it can serve as a guidepost for your efforts

to understand how corporate compliance works best in your company," Thus,

I hope that by sharing my own limited perspective, that I might also add some

value to that same understanding. Ok, as this is a post about compliance not

caveats, lets review:

The

report sets out to:

•

To provide compliance officers a

"comprehensive view of the ABC

risks they have.”

• To identify “the resources they have to fight them.”

•

And to demonstrate "how those resources are implemented

into compliance programs.”

Two findings

(among others) which were mentioned in the executive summary and which I will

also focus upon are:

•

The challenge that "third parties continue to vex compliance

officers."

•

The dynamic that "monitoring anti-corruption efforts on a

continuing basis is weak."

"Taming

Third Parties" as "the bane of anti-corruption programs."

As

the report states "taming third-party risks continues to be a major

weakness for anti-corruption programs, and the problem may well be getting

worse." Furthermore, there are a number of foundational hazards in third

party assessments and on-boarding procedures that may amplify those

difficulties. A few of those challenges

which I see as prevalent both before and during the on-boarding process are:

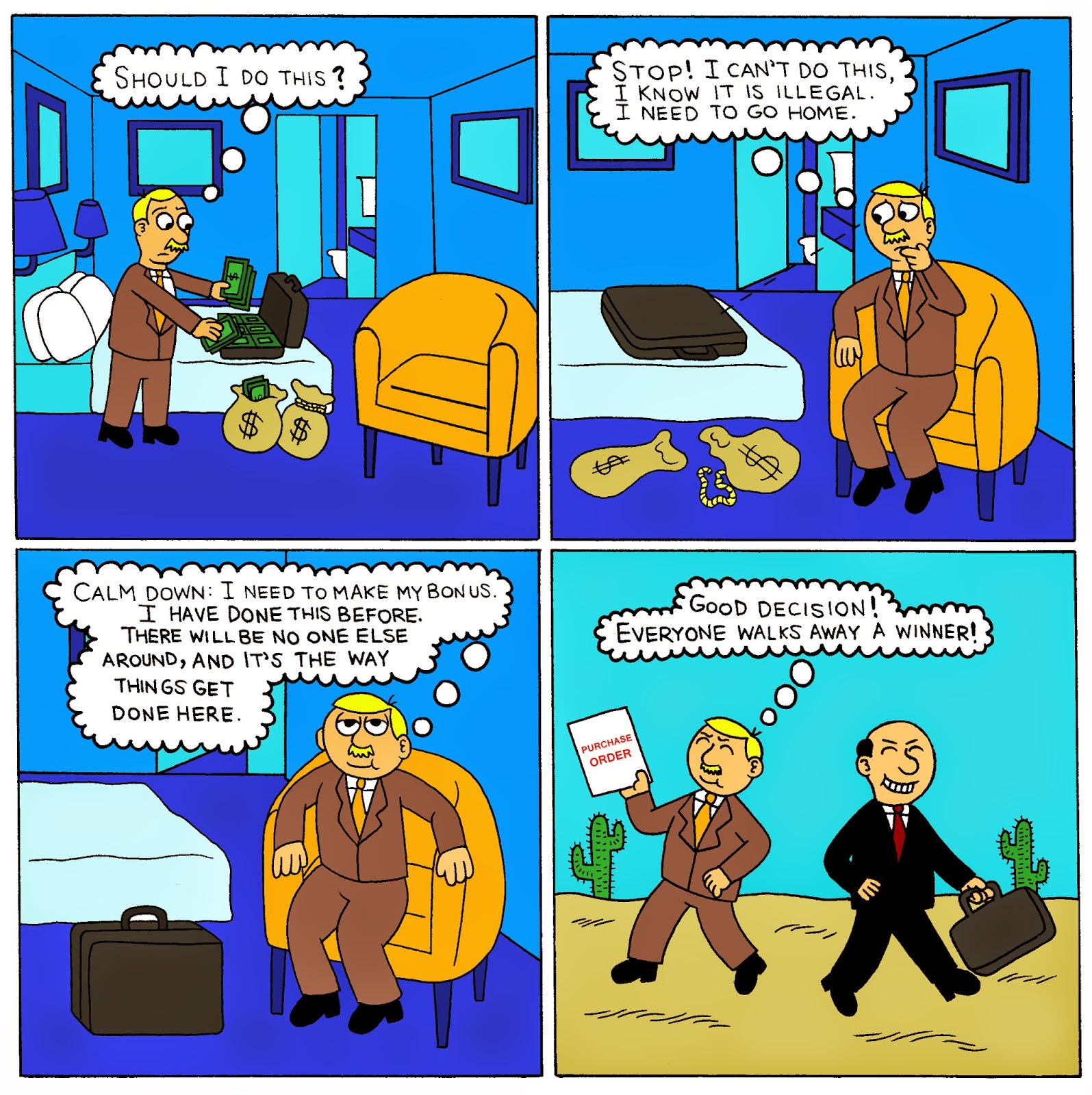

- "It's not my law" syndrome. There is an attitude among some third parties whereby they do not consider themselves as signatories or responsible to anti-bribery laws and acts. Thus, such intermediaries will have an attitude of "the law does not apply to me," or worse, "it is legal here." Where that corrupt approach exists before a relationship is even formalized, there is great peril for all involved. Those third parties which look at the vetting process with “corrupt intent” and which do not seriously undertake the legal obligations as put forth in investigatory and vetting processes, will simply do and say "whatever it takes" to get representation and corporate agreement finalized.

In

addition, where local data and in-country vetting resources which are in place

may also be corrupt, surfacing the ill will of such third parties who talk a

good game of “compliance” might be difficult, even with the best intentioned

assessment protocols. As Mr. Matteson Ellis states, in such areas,

corruption “might be baked into the economic order.” *

- Collusion with an internal sponsor. When an internal business sponsor, e.g. country manager, sales manager, etc., recommends an intermediary for onboarding, be additionally mindful of incentives, and the relationship between the sponsor and the intermediary. As Scott Killingsworth explains “it is not just difficult, but impossible, to be truly objective about a decision when we have a significant interest in the outcome.”** In my experience, where companies do not look into the motives behind such internal endorsements, companies would be well advised to listen to Mel Glapion, Managing Director, Kroll, and think about “sharpening the saw, and improving the processes and measuring that information that’s coming back to you.”

Indeed,

when you have an internal sponsor who recommends a third party for on boarding,

and who has a personal financial incentive for "short term success," the

risk of collusion between the sponsor and the intermediary during the vetting

process dramatically increases. When that occurs, detection of corruption is

severely hampered. In some cases, the company sponsor might actually

"coach" the third party through the assessment process in order to

insure the successful vetting of the intermediary. Such coaching might include

the sponsor assisting in the completion of third party self-assessment

paperwork and exams, sharing

confidential information about investigatory protocols, and overall interference

in the onboarding process.

Due

diligence and the life of a relationship

While

the report points to a positive trend in terms of companies that are conducting

due diligence on third parties, the contributors focus on an element of caution

in that "compliance officers were more confident in their ability to vet

third parties at the start of a relationship, and less confident in monitoring

third parties once that on boarding examination had passed." In fact, the

report shows the troubling statistic that "the numbers marched downward

for monitoring compliance after a relationship starts (43.3 percent), auditing

compliance of third parties (33.2 percent) and training third parties on

anti-bribery and corruption procedures (30 percent). “ That is a trend

fraught with great liability. Why?

- Impact of regime change. As Mr. Glapion, states, "people give good, very positive political statements about what they're doing, but if you scratch a little bit harder, what you see is that the follow-through doesn't support it." Or, as stated in the title "vet it and forget it." While Mr. Glapion recommends a four-year review and audit cycle, I would add that in regions with low integrity reputations, and where there is a regime change, such an event should trigger an automatic re-vetting protocol.

Governmental

turnover in politically unstable countries can often result in a change in the relationship

between third party representatives and government officials. As newly

appointed public officials take their place in the Ministries and

bureaucracies, prior corrupt relationships between intermediaries and their new

“friends in power” now come to resurface. Such a change in regime can

dramatically increase corruption risk, with the potential

consequence that today's "clean" intermediary could become tomorrow's

"corrupt" one, as this renewed relationship now comes into play

with respect to future business and transactions.

Mr.

Ellis refers to the hazards of such "touch points" with

government officials and state-owned employees as where “the incentives to

manipulate the process can be great.” Thus,

bribery risk is not necessarily a constant in the life of a relationship with

an intermediary. In low integrity

regions with “weak government institutions” (see Ellis), risk can change

abruptly, with a well-vetted legitimate business relationship in the past

turning into to corrupt one without warning, and worse, the corporation is

left unaware of this newfound exposure.

For

an entity which "vets and forgets" this is a dynamic which can occur

when the assessment process is not repeated after regime change or at least on

a regular interval, as the ABC Report recommends. In my experience, the

higher the risk, as measured by the regional or country corruption index, as

well as the market (in terms of exposure

to public officials), the greater the need for repeat due-diligence reviews

through either event triggers or articulated time intervals. Fact patterns are

often not enough to serve as future indicators, as changes of regime or ruling

party can have a significant impact on corruption risk.

As

Mr. Glapion recommends, corporations would be well advised to incorporate a

process which commands, lets "go and audit some of the companies that

either we reviewed three years ago or have been third parties of ours for a

long period of time." It is like those commercial disclaimers on well

performing mutual funds as "past performance is not indicative of future

trends." In addition, as the report indicates, there is no symmetry

between bribe and consequence, and investment in compliance over the long term

"pales in comparison to regulatory fines that can hit hundreds of millions

should a bribery offense go undiscovered."

In

conclusion, as the ABC Report states, “without that fundamental effort to

figure out what risks a company faces, building an effective compliance program

to address those risks becomes more difficult.” Hopefully, I added some value to that effort by focusing on the reality that some intermediaries don’t take anti-bribery and

corruption laws seriously, that they might collude with internal sponsors to

circumvent vetting processes, and that regime change can have a significant

impact upon where an intermediary might “sit” on the continuum of corruption. How

to deal with these potential gaps I leave to the experts, and would naturally

welcome and invite comment.

* “Regional Flavor: Crosscutting Corruption Issues in

Latin America” chapter eight: How to Pay A Bribe 2014 (Wrage, Alexandra

Addison). Mr. Ellis is Special Counsel, Miller & Chevalier.

** Killingsworth’s complete paper, ‘C’ Is for Crucible: Behavioral Ethics, Culture, and the Board’s Role in C-Suite Compliance, is available as a free download at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2271840. Scott Killingsworth is a Partner, Bryan Cave.

** Killingsworth’s complete paper, ‘C’ Is for Crucible: Behavioral Ethics, Culture, and the Board’s Role in C-Suite Compliance, is available as a free download at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2271840. Scott Killingsworth is a Partner, Bryan Cave.