In the

July 31, 2014 edition of the Jakarta Post there was a featured article “Smith & Wesson bribery scandal involves National

Police officers,” which reported that “the Indonesian Corruption Watch (ICW) has

called for an investigation into an alleged attempt by US gun-maker Smith &

Wesson to bribe officials at the National Police.” Such civil group

investigations into the “demand” side of bribery is very relevant to a recent

paper by

Transparency International (TI) called “Curbing Corruption in Public Procurement, A Practical Guide.” The TI paper, as stated in the on-line brief, “provides

government officials, businesses and civil society with a practical

introduction to the risks of corruption in public procurement.”

In

addition, the report “outlines key principles and minimum standards which, when

respected, can protect public contracting from corruption.” In my experience

and opinion, the Guide goes well beyond

that scope, and is an incredibly reflective representation of corruption

risks that are prevalent in international public procurement. Thus, I hope that

my comments, where I reflect on my encounters with such corruption, might lend

additional value to this already compelling work through the elevation of real

world examples and perspectives.

As

the report states in the introduction “few government activities create greater

temptations or offer more opportunities for corruption than public sector

corruption,” and the OECD estimates that “corruption amounts to between 20 per

cent and 25 percent of the procurement budget.” Thus, procurement corruption is

a problem and dynamic that exists both on paper and in reality, and as the OECD

points out, on a massive scale. While

the TI paper does an excellent job of breaking down public procurement into

four chronological stages, what I found resonating was the description of how

there is a continuum of corruption in terms of level and scale. The report

speaks of corruption by “low and mid-level public officials” (see prior post on

TI paper “Countering Small Bribes”) and “corrupt acts committed at a high level

of government.”

The

guide also calls attention to subtle forms of corruption that are used to

“manipulate budget allocations and project selection, even before the

contracting process begins.” Indeed, as the report calls out, such activities

occur “through the manipulation of eligibility criteria in the tender

documents, or having technical specifications that are biased and without

merit.” That description reminded me of a tender in the Middle East whereby the

delivery period as stated in the specification was prohibitively short, as

getting the necessary regulatory licenses after award would actually burn

through through the entire delivery period.

It was a requirement to which adherence would be impossible, or so I

thought.

Hello I must be going

I

travelled to the Middle East to meet with the procurement chief (this was a

substantial tender) and to see if this requirement could be changed as to allow

for a reasonable delivery period “after regulatory licenses” were secured. In

non-procurement speak, I was asking for a delivery period that would be fair to

all bidders, as no vendor could control how long it would take to get a

license. Well, as I sat there professing

the need for a modification, I noticed that on the chief’s desk was the approved and signed license for the

competitor, who was also the incumbent supplier. To get that license, the

competitor needed the end-user signature (being the person to whom I was

speaking), and that would have occurred three to four month prior. Thus, needing

no translator, and understanding what I was facing, I finished my coffee,

thanked the procurement official for his time, and departed.

That

is but one example of a public tender where one entity knew via corruption that

it was going to receive an award, and the procurement authority used a

restrictive delivery period as called forth in the tender document, to guarantee

the result. It takes two to corrupt, and I hope this example demonstrates how

both the supply and demand side work together to get a desired outcome, as the

Guide states “even before the contracting process begins.” While I don’t know

if a bribe was paid in my Middle East example, does it really matter, as the

process itself was corrupted?

Small

Island, big purchase

The

report talks of the “Financial Impact” of corruption, as “burdening a

government with financial obligations for purchases or investments that are

oversized, not needed or not economically justified.” This is a very real and serious issue, and I

have seen numerous examples of needless and wasteful purchases, some of which

were designed to facilitate corrupt transactions (sometimes it was just

disorganization and the output of inefficient procurement processes and

personnel). Either way, such

procurements do not facilitate the public good through the acquisition of

products and services that are needed by governments and hence, serve the well

being of the citizenry. I recall one

story of a small island nation with an outgoing leader who started a buying

binge prior to his departure from office. During that time period, there was a large

procurement of defense product, far

beyond what the tiny island could have needed for domestic security, and I

remember asking the sales manager, "what are they going to do with all that stuff?"

I

didn’t really need an answer, I knew this was wrong, and my question was rhetorical as part of my own

rationalization process. It was

certainly clear to me that the purpose of that procurement had nothing to do

with domestic security and it was nothing but an unnecessary purchase with corrupt intent under the

“umbrella” of public safety. A very

telling example, and as the report states, these are funds that “could be used

to provide or improve essential amenities and services” as opposed to

facilitating corruption for personal financial benefit.

Principles

The

paper sets out a number of principles that “minimize corruption risk” in the

procurement process, and a number of them resonated with me in the context of

my own experience but the one that caught my attention was professionalism. As the

report states, “where procurement officials are poorly paid, badly trained or

lacking a viable career path the risk of corruption increases.” Here we have a

dangerous dynamic from the perspective of trying to change corrupt procurement

environments. As Mr. Matteson Ellis states “when low-level government officials

are not paid enough, they sometimes rationalize seeking rent by other means.”*

Making their Pension

Where

you add regime change, which brings in a new group of procurement officials, it

is a recipe for procurement corruption on a number of levels. After these new

procurement officials get seated, they may aggressively seek bribes knowing

their employment might be of limited term due to the next changeover (as with

their predecessors). I remember one such

instance, post regime change, where an intermediary shared how there was going

to be a series of procurements, as new officials knew that they only had a few

years “to make their pension.” Accordingly, in such regions where you have low

paid officials, high turnover due to regime change, and a lack of training, I

see few solutions to this corruption spiral.

As described by Mr. Ellis, in such regions with weak state institutions,

“bribe requests might be baked into the

economic order.”

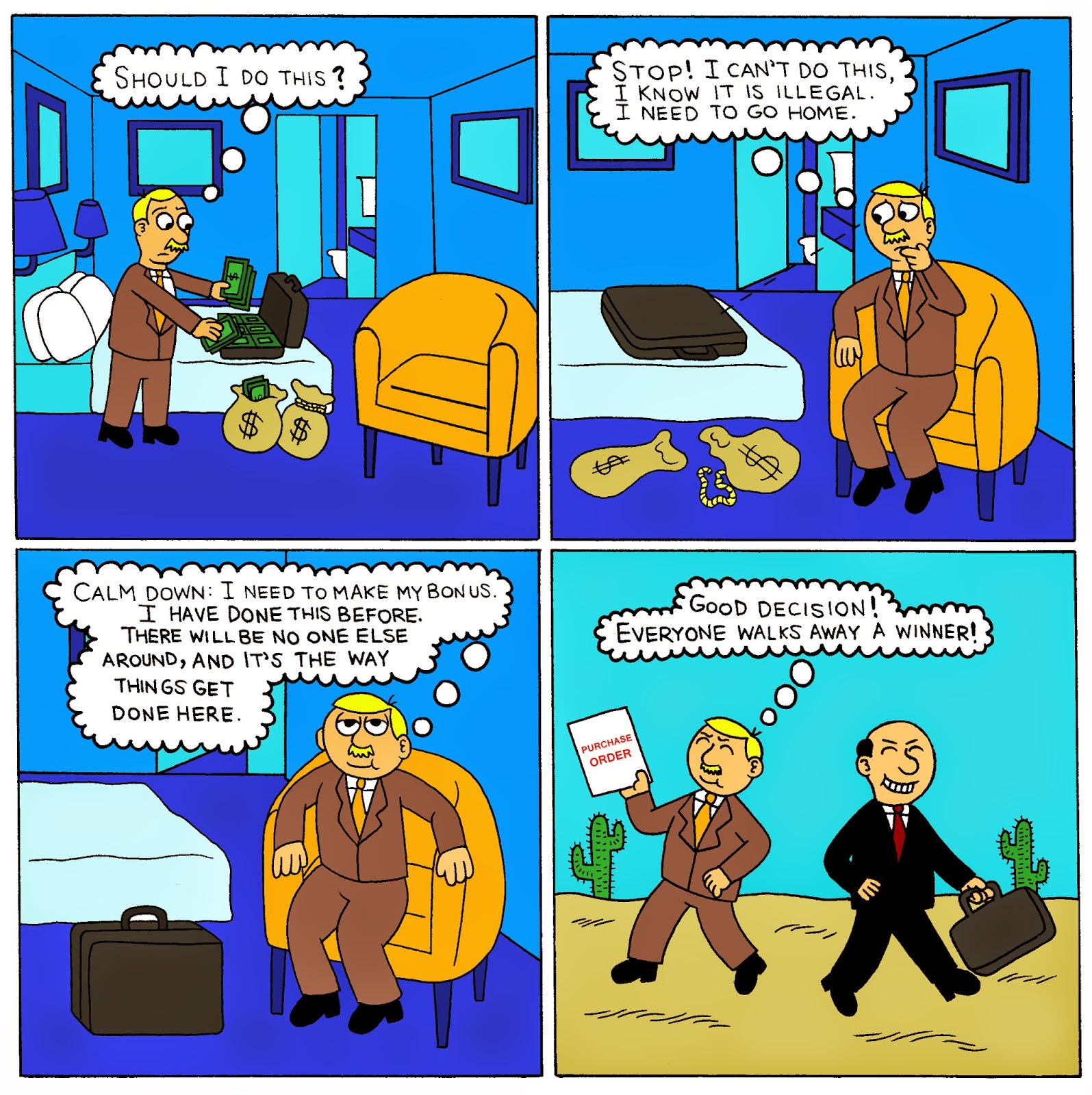

Like

the sales person on the front line of international business who may be looking

at a pay check that speaks to “win above all else,” for the procurement

official who sees nothing but opportunity to supplement what might be a meager

state pay-check, both sides now look at corruption as win-win. Small bribe or big bribe, this is a dangerous

dance for all involved.

Corruption in the Dark

As

the report states, “corruption thrives in the dark,” and “lack of information

on governmental activity and decision making can easily hide corrupt manipulation

of decisions in a procurement process.” So what can be done? Well, until

governments seek to address the issues of training, compensation and turnover

with respect to procurement organizations and personnel, perhaps the part of

the TI Paper called “Checklist for Government Officials,” (page 21, 3.2.) should be reviewed. This is a

critical section which was designed to highlight red-flags “about the integrity

of the process,” and which might also be a suitable guide for multinationals. In

other words, where those inherent procurement red-flags exist within a region,

country, or ministry, perhaps the corporation is well advised to “stay-away”

until those built-in institutional perils are addressed and changed.

Accordingly,

we are left with organizations such as Transparency International and those

like the Indonesian Corruption Watch, who are not going to let the issue of

bribery remain solely with the regulators at the individual and corporate

level. In my experience, corruption risk needs to be addressed through a

continued focus on international public procurements, as this is where the

“demand” side of corruption exists. My complements to TI for publishing the

Guide on Procurement; I found it surprisingly reflective of the realities “on

the ground” of international business.

* in How to Pay a Bribe “Regional Flavor: Crosscutting Corruption

Issues in Latin America,” which makes a very relevant companion guide to the TI

piece.