COPYRIGHT FOR ILLUSTRATION BELONGS TO RICHARD T. BISTRONG.

In

the June 2013 issue of Business

Compliance (Baltzer Science Publisher, Anthony Smith-Meyer, Editor), Scott

Killingsworth (Partner, Bryan Cave LLP) writes about “Ethics in the Executive

Suite: The Best, The Brightest and a Wicked Problem.”* The work is the first part of a two part series, and my focus

is on part one “The C-Suite Crucible and Behavioral Ethics.” In sum, the “wicked problems” of behavioral

ethics that this article focuses upon in the C-Suite, in my experience, are

also uniquely present in the thinking and behaviors of international business

executives who confront corruption on the front lines of international

business.

My

goal today is to call upon Mr. Killingsworth’s behavioral and organizational

paradigm to demonstrate how most of the dynamics that the article describes as

existing in the “environment of the C-Suite” are also prevalent with respect to

international business executives. I will use Mr. Killingsworth’s piece as an

intellectual companion guide to my own perspective of international business

misconduct, especially in the context of international bribery. Finally, before setting out on this journey,

when I speak of “international business executives,” I am referring to (from an

organizational chart perspective) those at the front line of international

business who also have group responsibility; thus, I refer to those who have supervisory

authority and direct reports along with associated P and L responsibility.

Mr.

Killingsworth isolates a number of elements as testing “the integrity of

executives,” and my focus is on those which I have seen elevated in the

thinking (including my own) of international business personnel. No single

issue dominants, for as Mr.

Killingsworth well states, when it comes to misbehavior “it seldom happens in a

single step.” Thus, I share my reflections on this work to expand upon our

understanding of how misconduct can so easily be rationalized, whether in the

C-Suite or in an overseas office of an intermediary. So, lets take a look under the hood of an

international business team, and see where the dynamics of misconduct might

exist.

- “The lure of large performance-based incentives” which can translate into “outsized temptations to do what it takes to obtain the desired results.”

As I

shared at the Dow Jones Global Compliance Symposium, where international

business executives have incentive compensation indexed to personal performance

in high-risk (corrupt) areas “compliance becomes bonus prevention.” As Mr.

Killingsworth states “here the notion of failing to “hit the numbers” or of

“losing” a bonus one has come to expect, or failing to close a sale that one

has considered likely, has obvious relevance: risk-taking increases and ethical

standards may sag.” In a public-company environment, that pressure gets

dramatically magnified at every quarter, as those pressures re-set from start.

Nonetheless, regardless of company size or public listing, the entire issue of

large incentive based compensation can create an inherent conflict of interest

when it comes to decision-making, for as Mr. Killingsworth affirms “it is not

just difficult, but impossible, to be truly objective about a decision when we

have a significant interest in the outcome.”

As

to the external setting, international procurements are often far and few

between, marked with unstable state institutions (see work by Matteson Ellis), creating

a “win big or lose big,” environment, with the obvious consequences upon

forecast and bonus. Where that bonus is

tied to personal performance, as Mr. Killingsworth states “escalating

commitment” may follow, where one takes greater risk to avoid loss (personal

and professional), and that is a process “that seldom ends well.” It is like

covering a bad bet with more money and a recipe forever increasing “small

bribes” to insure success.

- “The ability to operate with great freedom and little supervision.”

In

many organizations, supervision of international business leaders can often be

“out of sight, out of mind,” where such personnel have more discretionary

authority and operational freedom than their domestic counterparts. Having

spent the early part of my career in US domestic sales, I can state with great

certainty that as a domestic sales Vice President, I was subject to

dramatically more oversight and audit in my work, comparative to my subsequent

international responsibilities. I don’t think that was a unique experience,

especially when a company considers the domestic or home market as the “primary

market.”

I

have seen many organizations treat international sales as a “secondary-sector”

with the resultant impact upon supervision and discretionary authority for

international executives. Where managers retain such power, as Mr.

Killingsworth describes, it can be “difficult for subordinates or auditors to

see the entire process that adds up to a violation.”

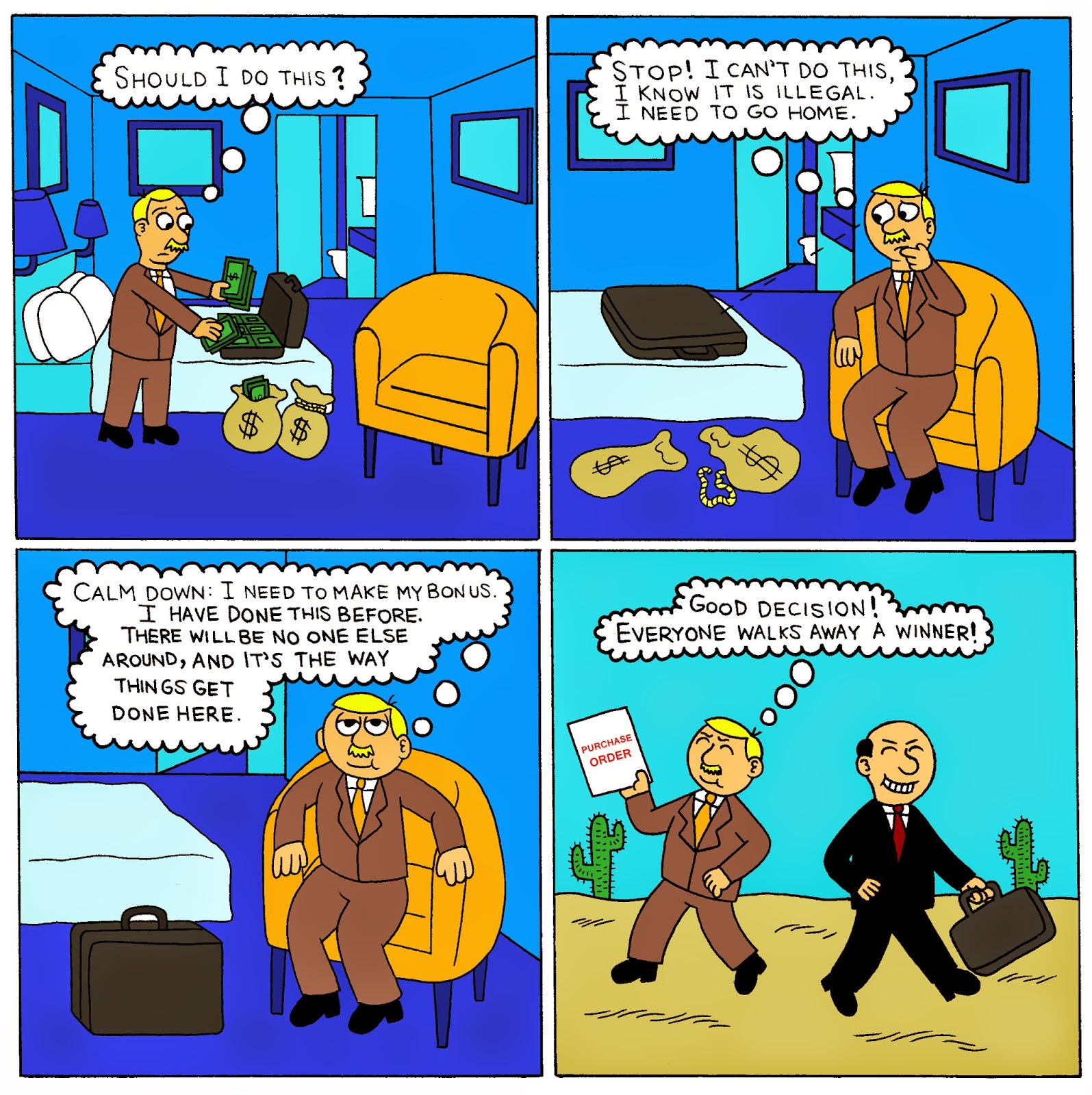

- The impact upon thinking "by early success in high-risk initiatives."

From

a personal perspective, this is a significant contributing element to risk

taking; thus, it is worthy of great consideration for those who have compliance

responsibility. Given the opportunity to get away with “small bribery,” (see

post on “Countering Small Bribes”) especially given that when the talk turns

to corruption on the front lines of overseas business there are often no

witnesses, that dynamic can have an enormous and calamitous impact upon future

thinking. How? As Mr. Killingsworth states, by “unwittingly

increasing risk appetite over time” and creating a “vicious cycle” of

overconfidence.

In other words, getting away with prior bad

behavior leads to great distortion when thinking about the consequences of

future corrupt transactions, as incremental risk “may lead to more serious

violations.” As Mr. Killingsworth

describes “where misconduct is justified by rationalization and reinforced by

success, small incremental steps can take us a long way.” In other words, once front line international

business personnel “dip their toe in the water” of corruption without getting

caught, and with financial success, a rationalization sets into the thought

process which starts to build momentum, and which then gets mixed into the

normal course of business thinking. It then often results in making “compliance

decisions on likelihood of detection.”

That

thinking reflects what Mr. Killingsworth describes as the dynamics of “if

nothing bad has happened, this is

evidence nothing bad will happen.”

Furthermore, this can “distort judgments of whether an activity is in fact

illegal and, more cynically, judgments of the likelihood that anyone will

notice the violation, or the severity of the consequences.” It is not my

perfect storm of rationalization, it is intellectual Armageddon.

- The thinking that a small infraction "does no one harm" and a belief that "the general rule does not apply."

In

prior posts, I speak of the illusion that bribery has no victims. Most front line business personnel do not consider

the impact of bribery upon local governance, standards of living, etc. They

might even think that they are helping those local public officials who are

very poorly paid by supplementing them with “small bribes,” and that the end

user still gets the best product and level of service. Sometimes bribery

results in the end user paying a lower price of goods and services, which

further distorts the illusion a “win-win.” When you add in the thinking that

“this is how it is done here” or “it is not even illegal here,” that makes for

a volatile mix of rationalization.

As

Mr. Killingsworth states “a suitable rationalization protects our positive

self-esteem and denies the reality that we have selfishly violated a rule.”

Indeed, when the thinking is that no one gets hurt by bribery, and that it is part of local norms, that rationalization

can easily win out over a more reasonable calculus to stay away from a

potentially corrupt and liberty threatening decisions.

- My own journey through self-deception

As

Mr. Killingsworth states, the sum of these factors, (along with others which

are in the article), are “like the weight of water against a dike,” and that

these variables “exert constant pressure on ethical decision-making at the top

of an organization.” Agreed. However, having never made it to the C-Suite, but

having described my own “perfect storm of rationalization,” this is a model

that has significant relevance to those who supervise and work with international

business executives. As Mr. Killingsworth’s describes, “where high stakes

combine with temptation, power, pressure, urgency and ambitious people under few

external restraints, a high-impact risk exists and must be addressed.”

As

for my personal reflection, well, as Mr. Killingsworth states “when we start

down the path of misconduct, the first person we deceive is usually ourselves”

and the attraction to “money, power, autonomy, recognition, attention and

status…may be strong enough to overpower allegiance to ethical or legal rules.”

Well said, and a difficult chapter in my own life which I

now can share with others.

* Killingsworth’s complete paper, ‘C’ Is for Crucible: Behavioral Ethics, Culture, and the Board’s Role in C-Suite Compliance, is available as a free download at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2271840. The abridged version published in Business Compliance as Ethics in the Executive Suite may be requested by contacting info@baltzersciencepublishers.com Subject: C-Suite ethics - Scott Killingsworth

No comments:

Post a Comment